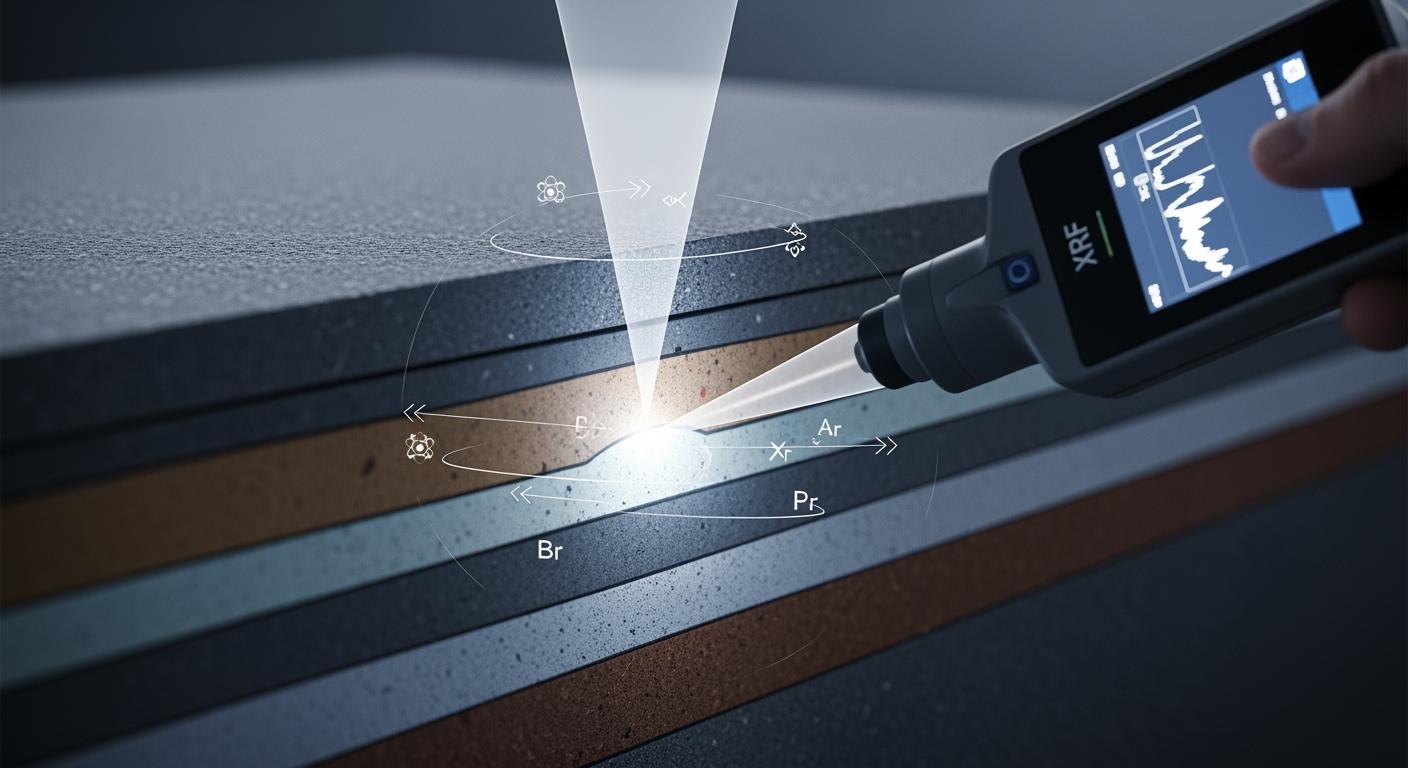

In the field of material science, X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) is revered for its non-destructive precision. However, a common misconception exists that XRF analyzes only the immediate surface of a sample. In reality, the analytical capacity of XRF extends into the material’s subsurface, a concept technically defined as “Penetration Depth.” Understanding this depth is critical for industries ranging from jewelry appraisal to aerospace engineering, as it determines the instrument’s ability to detect hidden layers, measure plating thickness, and identify sophisticated counterfeits like tungsten-filled gold.

This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the physics governing X-ray penetration, the factors that dictate information depth, and how to optimize XRF spectroscopic measurements for subsurface analysis.

Key Takeaways

Dynamic Depth: XRF information depth is not a static value; it is a function of primary beam energy, material density, and the atomic number of the elements being analyzed.

Critical Thickness: The depth at which 99.9% of the X-ray signal is absorbed is known as the “Infinite Thickness” for that specific matrix.

Heavy Metal Limitations: Dense materials like Gold and Platinum allow for very shallow penetration (micrometers), while lighter elements like Aluminum can be analyzed at depths of several millimeters.

Fraud Detection: Understanding subsurface analysis is the key to identifying “Smart Fakes,” where a thick gold plating hides a non-precious core.

Sample Integrity: Proper sample preparation and awareness of “Matrix Effects” are essential to ensure the volume being analyzed represents the bulk material.

The Physics of Information Depth in XRF

XRF analysis relies on the Beer-Lambert Law, which describes the exponential attenuation of photons as they travel through matter. When a primary X-ray beam enters a sample, it is absorbed and scattered. The fluorescent X-rays generated at a specific depth must then travel back through the sample to reach the detector. If the material is too dense or the generated fluorescent X-rays have too low an energy, they will be re-absorbed before they can ever be measured.

Critical vs. Infinite Thickness

In XRF, “Critical Thickness” is the sample thickness beyond which no further increase in intensity is observed for a specific spectral line. Once this point is reached, the sample is said to have “Infinite Thickness.” For analysts, this is the limit of the instrument’s vision. For example, when measuring light elements like Sodium or Magnesium, the critical thickness might be less than 1 micrometer. For a high-energy line like Lead K-alpha in a plastic matrix, the depth could exceed 10 millimeters.

Material Category | Typical Density (g/cm³) | Typical Detection Depth |

|---|---|---|

Low-Z (Plastics, Polymers) | 0.9 – 1.4 | Deep (Up to 15 mm) |

Middle-Z (Aluminum, Soil) | 2.6 – 4.5 | Moderate (1 – 5 mm) |

High-Z (Gold, Platinum) | 19.3 – 21.4 | Shallow (5 – 50 µm) |

Handheld XRF Capability | N/A | Surface to Subsurface |

Fundamental Factors Influencing Penetration

Four primary physical variables dictate how deeply a portable XRF analyzer can “see” into your specimen.

1. Primary X-ray Tube Voltage (keV)

The energy of the primary X-ray beam is the engine of penetration. A higher voltage setting (e.g., 50 kV) produces high-energy X-rays that can penetrate significantly deeper into a sample than a 15 kV beam. However, higher energy also increases the likelihood of “Compton Scattering,” which can create background noise in the spectrum.

2. Material Density

Density is the primary barrier to X-ray travel. In dense metals like Gold, the atoms are packed so tightly that they act as a massive shield. Fluorescent signals from even 1 millimeter deep are almost entirely absorbed by the gold atoms above them. This is why accurate XRF analysis of jewelry is considered a surface-to-near-surface technique.

3. Atomic Number (Z) of the Sample Matrix

The higher the atomic number, the greater the “Photoelectric Cross-Section,” meaning the material is much more efficient at stopping X-rays. Lead (Z=82) will stop an X-ray beam much faster than Iron (Z=26), regardless of the energy applied.

4. Energy of the Characteristic X-rays

Not all fluorescence is created equal. High-energy fluorescence (like the K-lines of Silver) can travel through significantly more material on its way to the detector than low-energy fluorescence (like the L-lines of Gold). Analysts must choose the correct spectral lines to get the desired information depth.

Typical Practical Depth Ranges

In industrial and commercial applications, knowing the exact information depth is vital for quality control. The following table provides the analytical range for various common coating and base material combinations.

Coating Element | Substrate (Base) | Typical XRF Measurement Range (μm) |

|---|---|---|

Gold (Au) | Nickel (Ni) / Copper (Cu) | 0.01 – 10.0 |

Silver (Ag) | Copper (Cu) | 0.05 – 40.0 |

Aluminum (Al) | Iron (Fe) | 1.0 – 150.0 |

Zinc (Zn) | Steel (Fe) | 0.1 – 60.0 |

The “Subsurface” Threat: Detecting Tungsten-Filled Gold

One of the most valuable uses of understanding penetration depth is in fraud prevention. Counterfeiters often use Tungsten (density 19.25 g/cm³) to mimic Gold (19.30 g/cm³). Because XRF’s penetration depth in pure gold is limited (approx. 10-20 micrometers for L-alpha lines), a very thick gold plating (e.g., 200 micrometers) could theoretically hide a tungsten core from a standard XRF scan.

However, professional tungsten detection protocols utilize the high-energy K-alpha lines of Tungsten. These X-rays are powerful enough to penetrate through the gold shell and reach the detector. If an XRF analyzer flags a Tungsten signal in a “24K Gold Bar,” it is an immediate indicator of a subsurface fake.

Professional Note: While XRF is unparalleled for surface and near-surface analysis, for very large bullion bars (1 kg+), it is best practice to combine XRF with ultrasonic testing to ensure the core is homogeneous.

Optimizing Accurate Measurement through Sample Preparation

Because XRF is inherently sensitive to the volume defined by the penetration depth, sample consistency is paramount. Avoiding measurement errors requires attention to surface geometry.

Surface Uniformity and Grain Size

If a sample has a rough surface, the X-ray path lengths will vary across the measurement area, leading to inconsistent results. For geological or ore samples, grinding the material to a fine powder (less than 75 micrometers) ensures that the analyzed interaction volume contains a statistically representative number of grains. In jewelry testing, ensure the sample is flat against the analyzer window to minimize the “Air Gap,” which can scatter low-energy fluorescent signals.

Polishing: Removes oxidation and “work-hardened” layers that may differ from the bulk metal.

Drying: Moisture in soil or ore samples absorbs X-rays and artificially lowers the measured concentrations.

Standardization: Use reference materials with a similar matrix to your sample to calibrate for specific information depths.

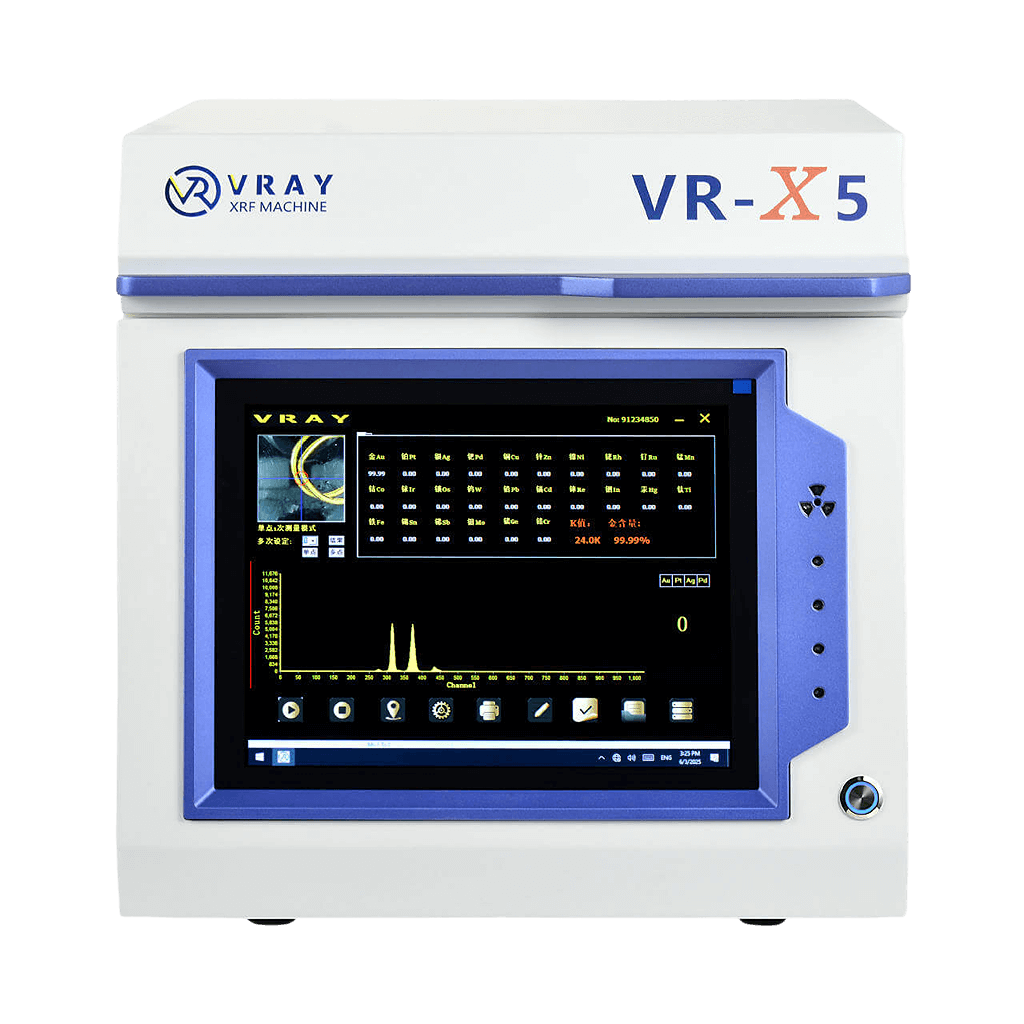

Did you know? Advanced Silicon Drift Detectors (SDD) used in VRAY Instruments are significantly more sensitive to the low-energy signals coming from the limit of the penetration depth, providing a clearer picture of the subsurface than older proportional counter technology.

Conclusion

Penetration depth is the “hidden dimension” of XRF analysis. By mastering the relationship between keV, density, and Z-number, analysts can transform their XRF device from a simple surface checker into a powerful tool for subsurface investigation. Whether you are verifying the valuation of antique jewelry or performing complex quality control on industrial coatings, awareness of your instrument’s information depth is the foundation of scientific accuracy.

Frequently Asked Questions

How deep does XRF go in a standard gold ring?

For most gold alloys, the analytical depth for Gold L-lines is between 5 and 15 micrometers. For higher energy Silver K-lines often present in the alloy, the depth can reach up to 40 micrometers.

Can XRF analyze through a plastic bag?

Yes. Because plastic is a low-density polymer (low atomic number), it is largely transparent to X-rays. XRF can easily penetrate thin polyethylene bags to analyze the metal inside, though it may slightly attenuate very light elements.

What happens if my sample is thinner than the critical thickness?

If the sample is too thin (e.g., a very thin foil), the X-rays will pass through it without enough interaction. The analyzer will report lower-than-actual concentrations. This can be corrected using specialized “thin-film” software calibrations.

Why is penetration depth deeper in aluminum than in lead?

Lead has a much higher atomic number (82) and density than aluminum (13). The high electron density in lead absorbs X-ray photons much more aggressively, stopping them near the surface.

Can X-ray energy be adjusted to see deeper?

To an extent, yes. Increasing the tube voltage (kV) generates more high-energy primary photons which penetrate deeper. However, the limit is still dictated by the absorption characteristics of the sample matrix.

For more professional insights into X-ray spectrometry and non-destructive testing, visit our VRAY Instrument Knowledge Base.